In my last post I discussed Baumol's cost disease and stated that it is having an enormous impact on the practice of law. In this post I want to discuss this impact in greater detail.

In my last post I discussed Baumol's cost disease and stated that it is having an enormous impact on the practice of law. In this post I want to discuss this impact in greater detail.Recap

By way of review, a basic observation of Baumol's cost disease is that the cost of some commercial services will rise faster than the rate of inflation. Stated differently, while some types of services may enjoy productivity gains, others will not--either because they cannot or because as a matter of policy we do not want them to. Over time, those services that do not experience productivity gains will grow relatively more expensive vis a vis other services and the average rate of inflation. Again, there is more discussion of this in my earlier post.

Think of all services, then, as being located along a spectrum: at one end are services that can benefit from improvements in productivity (such as assembly line work), and at the other end are those that cannot (or as a matter of social policy should not) see such productivity increases. And in the middle there is a big gray area in which the boundary between the two types is not so clear.

Effect of Baumol's Cost Disease on the Practice of Law

Now here's the key point I want to make: due to the rising cost of services that have not benefitted from productivity increases, there is pressure to figure out how to change the nature of these services so that they shift from one side of the spectrum to the other. Sometimes this is not possible, but sometimes it is. Moreover, such shifts make things extremely interesting in a highly lucrative service industry like the practice of law.

Think of it this way: some things lawyers do are resistant to productivity improvements, while others are not. For example, lawyers still need to go to court, just like they have for decades. You cannot send a "virtual attorney." Lawyers still take depositions. Lawyers still need to review documents and records pertaining to a transaction or a case. Computing advances may make it easier to transport or print such materials, but the materials still have to be reviewed and read by real people. So gains in productivity related to these activities are often limited to the development of expertise by the lawyers involved. Let's call these productivity-resistant services.

Other legal tasks are not productivity-resistant. Do you see the same type of cases over and over again? If you do, then you typically prepare standard-form contracts or pleadings. One might call these types of services productivity-receptive.

Productivity-resistant and productivity-receptive services thus share a common feature: productivity gains can be achieved through the application of expertise. The difference between the two, however, is in the fungibility of this expertise. Can the expertise be distilled down into written form--such as a standard-form contract or pleading, or into a software program--that can be applied to another, similar case or project? Can the steps needed to file a case or manage a corporate transaction be reduced to a "how-to" list that someone with less expertise (like a junior associate) can follow?

Stated differently, can the legal task in question be turned into something that we might consider a separate-standing article of commerce? Or is the task in question something more intangible or non-standard, and thus less fungible?

The difference is enormously important. Baumol's cost disease tells us that productivity-resistant legal services will become increasingly more expensive over time, as compared to productivity-receptive services. This means that as a general matter, there often will be pressure to reduce the cost of the former services by whatever means necessary.

Which gets us back to the gray area of our spectrum. The enterprising and entrepreneurial lawyer will figure out a way to reduce costs by making her services more productivity-receptive. Standard-form contracts, checklists for more junior people to follow in performing complex tasks like audits or due diligence, software programs--these are all ways to reduce costs. Some providers even sell their fungible products as stand-alone articles of commerce, as any trip to Books-A-Million or Barnes & Noble illustrates.

Lessons for Lawyers

So what lessons can practicing lawyers take away from this? There are many--but here are five that come to mind.

1. Do not stand still or be complacent. The lawyer who rests on his laurels will see his profit margins and stable of clients shrink. The dividing line between productivity-resistant services and productivity-receptive services is constantly shifting toward the productivity-receptive end of the spectrum.

2. Think of ways to make your legal services more productivity-receptive. If you are the first in your area (geographically or practice-wise) to do so successfully, you will have a leg up on the competition. It is no accident, for example, that fixed fees and other alternative billing arrangements are becoming ever more popular, since they are efforts to control rising legal fees. If you figure out a way to profitably provide legal services at these prices and your competitors cannot, you will be in an enviable position.

3. Embrace specialization as a way to lower your costs and improve productivity. Baumol's cost disease helps explain why the practice of law has become increasingly hyper-specialized. I personally have mixed feelings about hyper-specialization--I believe well-roundedness is a virtue in a lawyer--but it is an inescapable fact that one way you can improve productivity for productivity-resistant services is to become an expert in that field, since then you will need less start-up time on each project.

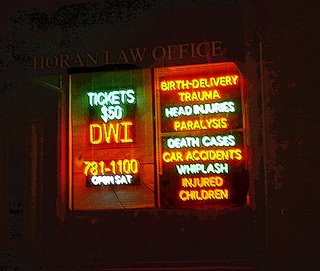

4. Understand that your competitors are not all lawyers. There is a good deal of debate about the merits of law practice being a monopoly, and in fact some of my previous posts relate to this subject (see here, here, and here) . But as formerly productivity-resistant services become productivity-receptive, and thus move toward fungibility, you will have competition not only from lawyers, but also from non-lawyers. Tax lawyers face competition from H&R Block and other non-legal providers. Corporate attorneys face competition from books and online publications containing standard-form contracts. And in some areas of administrative law practice (including my area of specialty, international trade law), you do not have to be a lawyer to represent companies or persons before governmental agencies. Your non-legal competitors may be serving the lower end of the client base and leaving the tougher, more challenging (and more profitable) matters for lawyers to handle, but that only proves my point even further.

5. Lawyers need to lower their costs in ways other than reducing the direct cost of their legal services. You have to pay the attorneys in your firm market-rate salaries, and your legal fees generally have to be within market parameters, but what about your building lease? Your retirement packages? The size of your staff? The billable hour requirements for your firm's lawyers--should they be increased? Decisions like these are often difficult to make, and I am not advocating a slash-and-burn or dictatorial approach to managing costs. I am, however, restating the obvious in a different way: profit = revenue minus costs. All other things being equal, the lower your costs, the larger your profit, and this becomes ever more important as the cost of providing legal services goes up.

*****

This is a subject that fascinates me. Baumol's cost disease offers a useful framework for thinking about recent and looming changes in the practice of law. And, for that matter, I think of it every time I unsuccessfully try to get service assistance at Home Depot or Walmart. While I usually cannot get someone who can help me with my questions, I can console myself with the fact that the absence of helpful personnel helps lower the cost of the goods I am trying to buy.

No comments:

Post a Comment